The Restoration of the Second Jewish

Commonwealth Backdrop to the 6 BC -33 AD Historical

Window Promises Rich Insights for Christians

by Mark Mountjoy

Abstract

This study examines long unquestioned assumptions projected upon the Synoptics and John subtly distorting aspects of their interpretation. Protestant biblical analysis has often unconsciously adopted an anachronistic Roman Catholic backdrop rather than consciously foregrounding the Second Temple era context from which these accounts genuinely emerged. Yet accurately apprehending the tumultuous Judean milieu circa 6 BC to AD 33 bears substantive implications for textual analysis.

By scrutinizing six key facets against an appropriate late first century BC and early and middle first century AD canvas, including contemporary officials, brewing socioreligious dynamics, Mosaic Law, contending dogmas, apocalyptic fervor and evolving messianic ideations, the thematic continuity threading the Gospels snaps sharply into focus devoid of homogenous filters. Passages long obscured by inherited paradigms bear surprising new resonance rightly synchronized with originally intended framing tied directly to unfolding rebel zealot activity and Jesus’ countervailing mission.

If Second Temple upheaval provides the actual stage upon which the canonical Gospel drama unfolded, should not interpretation transition accordingly? By confronting unconscious adoption of external anachronistic assumptions, perhaps long fractured theological discussions can freshly cohere when grounded back in the literal Judean caldron that ultimately spilled over into history altering cataclysm. At stake is attaining perspective capable of decisively cutting 21st century doctrinal knots by returning to the first century source.

Since the Reformation, dominant strains of Protestant biblical interpretation have unconsciously analyzed the four gospel accounts through implicit lenses tinted by a misleading Roman Catholic backdrop. But groundbreaking research now challenges long unquestioned assumptions about contextualizing Matthew, Mark, Luke and John that demand substantive revisions.

Far from merely disputing denominational minutiae, rightly recognizing the world from which the canonical gospels emerged bears surprising ramifications upending aspects of current New Testament scholarship. By abandoning anachronistic paradigms, fresh analysis of gospel texts reveals deeper insights into the motivations and meanings decisively shaping Jesus’ contentious ministry at a revolutionary first century crossroads culminating in the harrowing events of Golgotha and empty tomb.

This discussion aims not to needlessly undermine past interpretative traditions but rather highlight unintentional limitations that can finally be overcome by consciously transitioning to situate gospel narratives against the tumultuous Second Temple Commonwealth years rather than later developments unfairly read back onto the New Testament period. Do not such chronologically synchronized gospels warrant interpretative synchronization as well by rightly foregrounding the contemporaneous Judean context with eyes wide open to its import rather than filtered through external presuppositions? The answers may pleasantly surprise inquiring minds ready to peer through clearer windows into those momentous days in Israel which still echo through eternity.

The High Priest, Chief Priests and Levites

The "priests" addressed were not Catholic cardinals administering rituals but genealogical Aaronides like the high priest or Sadducees comprising Temple leadership. The human "commandments" challenging Jesus derived not from later catechisms but from contemporaneous Pharisees and their onerous oral traditions. Jerusalem itself, not the Vatican, bore blame for killing prophets and subsequent persecution of the early church. Moreover, John the Baptist's warnings of apocalyptic wrath targeted not Catholicism but that faithless generation, as judgment arrived amidst the [AD] 66-70 Jewish revolts seen by formerly skeptical Sadducees and Pharisees.

So from 6 BC to AD 33, the unified backdrop for the Gospels was the unstable Second Temple Commonwealth, not centralized Christianity yet to develop. Transitioning analysis to this revelation-rich era yields major hermeneutical and applicational insights. For instance, Command-Example-Necessary Inference (CENI) offers a principle for responsibly deriving doctrines based on New Testament patterns. But conventional applications often unconsciously default to anachronistic paradigms distorting text. Properly realigning context resurrects discussions about interpreting messianic prophecies through original audience eyes to maximize legitimate scriptural authority and unity.

The above summarizes the essay’s goal of consciously recentering analysis of the four Gospels around the tumultuous Second Temple period from which they emerged rather than readings homogenized through an ersatz church lens.

Who was the High Priest?

The High Priest during Jesus’ trial and crucifixion was Caiaphas, appointed by Valerius Gratus, the Roman Prefect under Tiberius, around AD 18. He subsequently held this office for 18 years until AD 36. As High Priest, Caiaphas served as president of the Sanhedrin and regulated duties in the Second Temple where sacrifices occurred.

Who Were the Chief Priests?

The chief priests largely belonged to elite priestly families historically tracing back to the priesthood's formation under Moses’ brother Aaron. They were drawn from the Sadducean sect who ran the Temple. In the first century, chief priests wielded control over Temple activities and oversight over many administrative, fiscal and legal religious matters vital to Jewish life under Roman occupation.

Who Were the Levites?

Levites, descended from Levi’s son Kohath, assisted in various subordinate Temple roles. They sang psalms during services, guarded temple treasuries, supervised building maintenance, checked sacrificial animals as ritually clean, among other duties supporting ongoing worship and functions. Levites' prominence severely declined under King David and Solomon’s reorganization which elevated the lineage of Zadok (a High Priest descended from Eleazar) but they still assisted the Aaronid priesthood in the Second Temple period.

So in summary, appreciating distinctions around Temple hierarchy and responsibilities provides helpful social, political and theological context indispensable for properly situating activity and tensions depicted in accounts of Jesus' ministry tied directly to contemporary leadership among competing Jewish sects vying vigorously for leverage and power in that volatile era.

Who Were the Sadduccees?

The Sadducees were Levites who emerged as a powerful group of elitist priests, aristocrats, and merchants during the Seleucid rule of Judea in the 2nd century BC. They later held sway in the Temple and Sanhedrin court under the Ptolemies and Romans through cooperation with occupiers.

Philosophically, the Sadducees rejected beliefs beyond the written Torah, denying concepts like resurrection, angels, and spirits as irrational corruptions violating God’s transcendence. Their rationalist theology clashed with popular Pharisaic supernaturalism and messianic zeal. They interpreted Torah rigidly, only affirming doctrines with direct textual attestation and repudiating notions of an afterlife.

As Hellenized sceptics, Sadducees deemed miracles and prophetic sign gifts either impossible infringements of natural order or manipulative sorcery threatening social stability. Their suspicion of charismatic wonder-working fed tensions with more spiritually demonstrative groups. By Jesus’ day, collaboration with Rome cemented Sadducees as despised establishment elites overseeing the Temple while suppressing movements jeopardizing their privilege and power.

In conclusion, the Sadducees emerged under Seleucid rule as uncompromising scriptural literalists who, through allying with occupiers, dominated Judean affairs and Temple worship. They denied resurrection and angels as irrational corruptions of revelation. Similarly, prophetic signs were deemed either supernatural violations of divine order or subversive magical frauds. This hostile rigidity toward charismatic marvels seeking liberation from oppression exacerbated conflicts with Zealots and early Christians alike.

Who Were the Pharisees?

The Pharisees emerged as a renewal movement during tumultuous Hellenization imposed upon Judea by Antiochus IV Epiphanes of the Seleucid Empire in the 2nd century BC. Their scriptural literalism and supernatural beliefs opposed growing Greek philosophical influences threatening Hebrew practices.

Specifically, the rural priest Mattathias (Hasmonean dynasty founder) rebelled against assimilative decrees banning customs like Sabbath observance, circumcision and kosher laws. This grassroots armed resistance, later led by Mattathias’ son Judas Maccabeus, became known as the Maccabean Revolt. Though initially motivated by politics not theology, the Maccabees’ eventual Temple purification and rededication established them as heroes defending faith against foreign contamination.

The Pharisees arose from activist remnants of this liberation struggle who continued advocating strict Torah adherence once the priestly Hasmoneans consolidated ruling power. They promoted popular piety and angelology grounded in Persian-influenced apocalyptic hopes, in contrast to aristocratic Sadducees who accommodated external philosophical currents dismissive of supernatural dimensions.

In essence, the Pharisees coalesced from former militants endeavoring to preserve ancient revelation against creeping foreign religions and philosophies that eroded monotheistic faith expressed through righteous obedience. Their supernatural beliefs fueled apocalyptic passion for divine deliverance from occupying forces seen as judgments upon impurity likewise demanding spiritual zealotry centered on Torah and Temple.

This movement birthed Rabbinic Judaism after Rome quashed unrest in the Province of Judea. But initially Pharisees fought worldliness through rigorously upholding Mosaic piety they believed birthed previous divine liberation. Their origins illuminate motivations colliding with Early Christianity’s claims to fulfill ancient hopes.

Are the 'Scribes' and the Essenes One and the Same?

An intriguing hypothesis suggests the oft-mentioned “scribes” in Gospel accounts actually refer to the Essene sect, not merely professional copiers of biblical manuscripts as typically presumed. This identification is based on Second Temple era discoveries like the Dead Sea Scrolls evidencing isolated, ascetic communities of devout copiers withdrawing to the Judean wilderness. Known as the Qumran Essenes, these monastic rebels opposed the compromised Temple establishment. They focused on ultra-strict Torah interpretations, ritual purification, celibacy and communal living while awaiting apocalyptic deliverance from foreign corruption. The Qumran site housed a scriptorium where priestly volunteers painstakingly produced sacred texts, especially divergent Pentateuch editions supporting the Essenes’ uncompromising theologies.

If the Synoptic scribes teaching alongside Pharisees indeed reference such separatist settlements consumed with perfecting and expanding scriptural scrolls amidst a hostile world awaiting imminent judgment, it further clarifies religious tensions and movements colliding in early first century Palestine. Additionally, the theory illuminates why Jesus garnered accusations of threatening to destroy and rebuild sacred institutions undergirding society. Intriguingly tying Gospel figures firmly to known groups illuminates polemical subtexts infusing disputes recorded in these biographical accounts as factions vied vigorously for authority amongst eschatological turmoil.

Intriguingly, the separatist sect behind the Dead Sea Scrolls overtly spurned Temple rituals under corrupt priesthoods. Their founder, the Teacher of Righteousness, condemned the establishment all the way back to Hasmonean ruler Alexander Jannaeus in the first century BC. This dissent drove them into the desert to await messianic vengeance against foreign collaboration. Believing purity was irrevocably defiled, the Essenes developed alternative purification rites and lived in monastic exile feeling only they embodied the true, faithful remnant of Israel. Given pride in their uncompromised convictions, Essene identification as the scribes Jesus debates and promises to replace frames mounting conflicts in a revealing light.

The Essenes expected their own Teacher of Righteousness to return as a conquering messiah-king who would vindicate their sect as God’s chosen community. Jesus likely struck Essenes as a dangerous fraud usurping their destiny. Similar to how Pharisees felt preempted, Essenes had their own apocalyptic aspirations his unorthodox claims directly challenged. Placing Jesus amidst seething internecine rivalries renders unintelligible aspects of the Gospels coherent.

A Word About the 'Herodians'

Despite routine presumption, the canonical Gospels display little fixation upon Imperial Roman figures like emperors or procurators. These writings emerged from Roman Judea yet  focus not on colonial masters but faith disputes with other Jews. Jesus' trial scenes highlight collusion between the high priestly Sadducees and Roman officials. However provincially imposed leaders play supporting roles in the Passion drama.

focus not on colonial masters but faith disputes with other Jews. Jesus' trial scenes highlight collusion between the high priestly Sadducees and Roman officials. However provincially imposed leaders play supporting roles in the Passion drama.

Of more direct concern to the Gospel authors were the Herodians - partisans of regional Herodian dynasty retaining a measure of autonomy under external oversight. Beginning with ruthless Herod the Great, the Herods rebuilt the Jerusalem Temple to consolidate popularity. His offspring, namely tetrarchs Philip and Antipas featured in several Gospel events, warily monitored potential threats near their remaining lands.

The Gospels report the Herodians particularly perturbed by Jesus' miraculous works which enhanced his influence at their expense. Though despising the nationalistic Pharisees, the Herodians jointly schemed with them to discredit and eliminate Jesus before enthusiastic crowds began seeing him as rightful heir to the Hasmonean priest-kings whose authority Herod had usurped through Roman sponsorship. They preferred to silence Jesus themselves rather than risk Pilate interceding if acclaim grew beyond containment.

So the canonical Gospels manifest local anxieties, identifying Herodian overseers – not distant Roman magistrates - as spearheading lethal schemes to protect regional power from untampered charismatic preachers and wonder workers whose activities seemed to signal the end of their fragile dynasty's sway if left unchecked.

Framing Synoptic and Johannian

Eschatology into This Semitic Framework

Now, John the Baptist's warnings in Matthew 3:2-12 spoke not of future Catholicism but the imminent judgment facing the Second Temple Jewish establishment; far from vaguely targeting developments centuries hence, John the Baptist’s blistering prophecy of wrath (Matt. 3:7-12) condemned leaders jeopardizing an entire civilization on the cusp of horrific cataclysm. By consciously and patiently foregrounding the Second Temple timeframe, we witness John the Baptist's scorching denunciations snap into crystallized focus as last gasp alarms delivered to steer Judea’s faithless shepherds away from an abyss mere years ahead.

John’s ministry straddled the transition from Herodian custodianship to direct Roman procuratorial rule over simmering factions in Palestine. His listeners held power enabling either explosive revolt or potential revival before the prophesied Anointed One emerged to reward the righteous and weed the nation (Matt 3:12).

As a judgment preacher, John exploited ritual baptisms, prophetic oracles and ethical polemics to provoke urgent repentance in light of temporal proximity to the winnowing Son of Man holding his winnowing fork (Matt. 3:10-12). His neighbors knew the Scriptures promising fire against the barren and fruitless (Ezek. 15:1-8).

Once transposed into first century Judean turmoil, John’s sobering call to bear fruit befitting repentance (Matt. 3:8) reemerges as a last invitation to lead reform, making Jesus’ way smooth rather than perish under Pilate’s sword or in sectarian chaos destined to engulf that generation after rejecting the day of visitation (Luke 19:41-44). So early Gospel layers resound with John’s unheeded pleas forestalling religious meltdown.

A Second Look at the Apocalyptic

Sayings of Our Lord

With the proper historical context consciously established, we're now equipped to re-examine Jesus' apocalyptic proclamations and warnings in the Gospels with fresh eyes. His provocative messianic claims and foreboding predictions come into sharper relief when removed from intervening filters and grounded back in the original turmoil filled setting tieing directly to religious power dynamics and revolutionary unrest in first century Judea.

Having reoriented interpretation around the Second Temple period from whence these accounts emerged, we can proceed scrutinizing dramatic statements by Jesus with greater recognition of what originally imbued these declarations with such explosive significance amidst the prevailing climate of eschatological anticipation and factional tension. His layered references to judgment, spiritual authority, destroyed and restored temples and collapsing old orders transport modern readers right into the heart of risky controversies playing out through the ministries of both John the Baptist and Christ himself as competing groups wield scriptures and wonders to jockey for position awaiting the climax of the ages.

Just as present communication benefits by shared vocabulary, so too comprehending the Gospel record rests on properly understanding the lexicon of concerns defining that era. Therefore, with due contextual groundwork laid, we are fortuitously equipped to press forward tackling long convoluted debates over specific passages through a long overdue shared frame of reference designed to uncover substantive new interpretative agreement hidden in plain view as though strangers lacking common tongue. Please let me know your thoughts on the possibilities ahead given this preparatory foundation strengthening communication through consciously transitioning to the original situational setting informing the New Testament accounts.

Seeing What Is Hidden in Plain Sight

Without enumerating every disputed detail, Christians can chart their own course revisiting Synoptic and Johannine passages afresh. The contours emerge through observing judgment upon faithless “children of the kingdom”/“tares” in Matthew 8 and 25, Satan returning amidst desolated rebels (Matt. 12:43-45), human traditions supplanting God’s law (Matt. 15:1-20), and repeated timeframe delimiters on seeing the Son of Man epitomized in the Olivet Discourse (Matt. 24; Mark 13; Luke 21).

Christ’s apocalyptic declarations recur in the Gospels because they defined his ministry as controversies careened toward the era’s disastrous denouement. The Sanhedrin interrogation (Matt. 26:62-66) distills the central conflict - would deity endorse Jesus’ messianic forewarning? Pilate chose immediate expedience; history recorded the results.

Transitioning interpretative paradigms centered on the initial Judean setting unveils afresh how the Gospels intertwine narratives advancing toward Jerusalem’s reckoning with rebellious elements that ushered in her downfall. What emerges is rediscovering Jesus amidst sectarian storms, beyond denominational depictions. As clouds of war gather, with arguments full and passions high, Jesus prepares his followers spiritually through establishing symbolic communion commemorating his coming sacrifice, while interceding through an extended prayer recorded in John 17 petitioning for their protection, mission and unity following his departure.

Related

[Click the image]

The Nature of the Emergency in the Catholic Epistles

The Fig Tree of the Olivet Discourse

CENI, Eschatology & a Proper Understanding

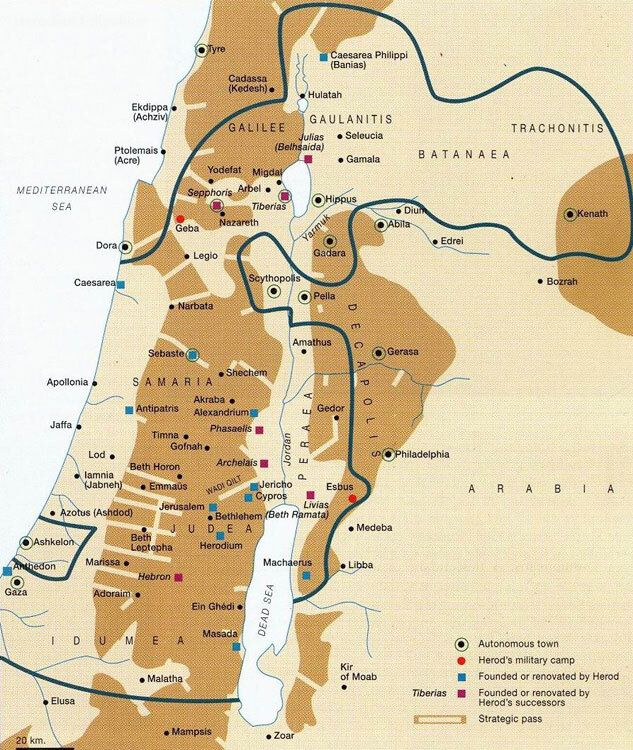

Map of Herodian Judea, which realized and enforced Roman rule upon the Holy Land after Herod the Great usurped political authority from the Hasmonean Dynasty under the sponsorship of the Roman Republic in 37 BC.