For Christians, CENI Defines and

Explains Questions About Eschatology,

Hamartiology, and Orthodoxy

by Mark Mountjoy

Hermeneutics and CENI, which stands for Command, Example, and Necessary Inference, are like two sides of the same coin when it comes to understanding and interpreting religious texts, particularly within the context of Christianity. Hermeneutics is the study of interpretation—it's all about understanding the meaning behind written texts, considering factors like historical context, cultural background, and language nuances. It's a broader approach that seeks to uncover the deeper meanings and intentions of the author. Imagine stepping into a library filled with ancient scrolls, manuscripts, and texts—each holding stories and wisdom from civilizations long past. As you pick up a dusty volume, you realize that understanding its true meaning isn't as simple as reading the words on the page. This is where hermeneutics comes into play.

Hermeneutics is like being a detective, tasked with unraveling the mysteries hidden within the pages of history. It's not just about reading words; it's about delving deep into the context, culture, and language of the author to uncover the true message behind the text.

Think of it as a journey of exploration and discovery, where every interpretation brings us closer to understanding the heart and soul of the author. It's a process that transcends time and space, connecting us with the thoughts and intentions of those who came before us.

In a world filled with diverse perspectives and interpretations, hermeneutics serves as our guide, helping us navigate through layers of meaning and significance. It's about more than just decoding ancient texts; it's about gaining insight into the human experience and discovering universal truths that resonate across generations.

So the next time you pick up a book or scroll, remember that hermeneutics offers us the key to unlock its hidden treasures. It's a journey of discovery—one that invites us to explore the rich tapestry of human thought and expression woven throughout history.

On the other hand, CENI is a specific method of interpretation commonly used by some Christian denominations. It focuses on extracting principles or commands directly from the text, as well as looking for examples and necessary inferences to guide belief and practice.

So, how do hermeneutics and CENI relate to each other? Well, you can think of hermeneutics as the foundation upon which CENI is built. Hermeneutics provides the tools and framework for understanding texts in their original context, while CENI offers a systematic approach to applying those insights to contemporary beliefs and practices. In essence, hermeneutics helps us grasp the broader meaning and significance of religious texts, while CENI provides a practical method for applying those insights to our everyday lives as believers. Together, they form a powerful combination for interpreting and applying sacred scriptures within the Christian tradition.

Examples of the urgent need to apply CENI principles to Bible eschatology:

Six centuries before Christ Gabriel told Daniel to ‘seal up the prophecies’ till the end, because it was not near (Dan. 12:8-10) But the Apostle John, twenty centuries ago was told not to seal his prophecies because the time was near (Rev. 22:10). What is the NI about these two instances?

Jesus said, If you continue in my word, then are you my disciples indeed, and you shall know the truth and the truth shall make you free - John 8:31. Then why is NI and eschatology the ‘off ramp’ where this interpretive principle somehow must be abandoned on difficult but Scriptural questions about the New Testament Christian understanding of Bible prophecy? Why is it excluded and the New Testament’s own claims are suddenly taken with a grain of salt?

NI and the audience relevance inferences of Matt. 10:23; 16:27-28; 24:34 and Luke 23:27-31; 1 Cor. 7:26, 29-31, cf. Rev. 6: 12-17 are passages that give us something to grapple with. How far can an span of time extend to be able to allow the contemporaries of Jesus and the daughters of Jerusalem and their children live long enough to see the Sixth Seal of Revelation chapter 6? And if they died without that happening, what does that do to Jesus’ prophethood and the inspiration of the New Testament itself?

CE demands that Christians be impartial in their judgment, but do the examples of the Bereans (Acts 17:11) and the command of Paul in 1 Cor. 4:6 and 1 Thess. 5:21 exclude eschatology where Christians, according to their own preferences, can pick and choose what they will accept and what they will reject?

Can NI resolve a day ‘as a thief’ intersecting with the lives of individuals who lived in first century Thessalonica? - 1 Thess. 5:1-4; 5:23-24

Some Christians believe the Papacy and popes fulfill Paul's prophecies in 2 Thessalonians, but how can NI explain how the man of sin could be being restrained in the first century if he was not also born in the first century? 2 Thess. 2:7. And would this not also exclude Pope Boniface III who was born circa 540 AD?

How does NI frame the threat of the coming of Christ ‘as a thief’ on the eve of the Destruction of Jerusalem? Rev. 16:5 cf. Matt. 24:42-44 and 1 Thess. 5:1-4; 5:23-24.

Does NI allow that the kingdom of God was at hand in the first century, but the Second Coming of Christ was NOT at hand at the very same time? Rev. 1:1, 3, and 7; Rev. 2:24-25; 3:10-11; 22: 6, 7, 10, 12 and 20.

Would the NI criterion demand a review and revision to the arbitrary assignment of Babylon the Great (Rev. 14:8, 16:19, 17:1-18, 18:1-24, and 19:1-4) to Roman Catholic or denominational entities? Would an improved hermeneutic factor in such passages and verses as Matthew 23:29-39; Luke 9:31; Luke 11:45-51; Luke 13:33; Acts 7:52-53; Gal. 4:21-31; and 1 Thess. 2:15?

Can the CENI hermeneutic define the reasons why the interim of Satan’s incarceration cannot be intertwined or posited anywhere in the Gospels, Acts, or epistles-or the first 19 chapters of the Book of Revelation: Luke 22:3; Acts 5:3; Ro. 16:20; 1 Cor. 5:5; 2 Cor. 4:4 and 11:14; Eph. 2:2; 1 Thess. 2:18; 2 Thess. 2: 2:9; 1 Tim. 5;15; Jas. 4:7; 1 Pet. 5:8; Rev. 2:13; 12:3-17; 13:2-4; and 16:13-14. These passages and verses arguably document Satan’s whereabouts before he was ever cast into the bottomless pit at Revelation 20 verse 1. So what does that mean for how Christians determine the beginning of the millennial period that is traditionally laid across the whole period from 33 AD till the eve of the end of time itself?

A closely related issue is this: Does NI preclude that Revelation 20:4 could begin anywhere in the Book of Acts, as the majority of Christians presently believe? Does not the necessary inference of Rev. 20:4 direct us to issues first raised and dangers first mentioned only in Revelation chapter 13:15 and thereafter?

In conclusion, these selected examples highlight areas where applying a CENI interpretive framework in relation to eschatology could yield exegetical and hermeneutical progress. Comparing closing instructions to Daniel versus the Apostle John raises scope questions given the passage of seven centuries. So do multiple passages tightly focused on temporal nearness and unfolding of events in the lifetimes of Christ’s original audiences. Command-Example-Necessary Inference calls into question why commentary on prophecy differs from treatment of doctrinal materials when the same principles governing sourcing truth claims apply. If objective methodology consistently determines practice across belief systems, on what grounds can entire categories like eschatology diverge into selective analysis?

Rather than isolated proof-texts, thematic traces through Hebrew Scripture and Revelation spotlight potential for clarifying long-contested identification of religious institutions based on repeated contextual references and frames. Historic figures could not fulfill prophecy hundreds of years before being born. But evidence indicates Satan remained loose, not bound, during periods traditionally deemed a millennium of incarceration.

In short, credible application of agreed hermeneutics across biblical genres and eras promises to resolve certain enduring uncertainties through evenhanded investigation free of confirmation bias. Sincere truth-seeking Christians across all backgrounds should therefore welcome whatever conclusions arise when established interpretive guardrails govern prophetic discussion as much as any other.

Ironic Prevailing Developments

That Defy CENI Logic

It is indeed ironic when those upholding the straightforward claims of Scripture regarding fulfilled prophecy face accusations of heresy from Futurist interpreters. Yet four key passages illustrate that the New Testament itself anticipates this situation:

Matthew 18:15-17 upholds the practice of coming to a sister or brother individually when a perceived "trespass" occurs to restore them gently. Only if they refuse correction is the matter to be brought before the church. Yet fulfilled prophecy aligns with sound interpretive principles, so there are no grounds for charges of error.

Titus 3:10-11 warns that a divisive person should be admonished twice before being rejected, which assumes their teaching is problematic. Yet clinging to the timing indicators within Scripture itself cannot reasonably be deemed heretical.

James 5:19-20 praises turning back one who wanders from truth to save their soul from death. Yet Atavist eschatology stems from following textual markers about the nearness of fulfillment. So it is not a trek away from early Christian claims but a courageous acceptance of them.

Finally, 2 John 9-10 is often cited to claim that realized eschatology denies Christ by not abiding in the "teaching of Christ." Yet expecting the imminent fulfillment clearly articulated in the New Testament matches His eschatological teaching.

In summary, holders of Atavist interpretations are blameless when charged with error or heresy. They draw their conclusions from the text rather than imposing external ideas upon it. Steadfastness is warranted despite objections, since their views derive from Christ Himself as articulated in Scripture. Any discord or disunity resulting comes from refusing to consistently apply sound CENI interpretive principles to prophetic passages.

Without adhering to CENI principles, the genuine New Testament doctrine of Christ's return to hinder the Zealot wars might be condemned as a grave sin by those who don't apply such interpretative rules. On the contrary, interpretations of eschatology that deviate from New Testament beliefs, without the application of CENI, could be perceived as 'acceptable' and 'orthodox,' despite straying from established biblical teachings.

In essence, the absence of CENI principles in the study of eschatology could lead to a situation where orthodox beliefs are deemed sinful, while unorthodox interpretations are accepted as valid and consistent with Christian norms. This highlights the importance of employing consistent and rigorous hermeneutical principles in interpreting biblical prophecy.

Things Christians on Both Sides

of the Debate Must Not Do

In the face of accusations and pressure to renounce New Testament eschatology, it is imperative for believers to stand firm and unwavering. The texts provided, such as Matthew 18:15-17, Titus 3:10-11, James 5:19-20, and 2 John 9-10, outline the process of addressing disputes within the church. However, if one's understanding of eschatology aligns with the New Testament teachings, yielding to coercion would mean forsaking the truth of God's Word. When individuals bring accusations or suspicions of heresy against those who uphold New Testament eschatology, irony prevails. The irony lies in the fact that those accusing others of deviating from the truth may themselves be misunderstanding or misinterpreting the Scriptures. Christians who adhere to the New Testament's teachings on eschatology should not yield to such pressure, as their conviction is grounded in a careful examination of biblical texts and adherence to accepted standards of hermeneutics.

Furthermore, the understanding of eschatology is closely linked to hamartiology, the study of sin. If one's understanding of eschatology is flawed, it could lead to a distorted view of sin and salvation. Therefore, it is essential for believers to hold fast to the New Testament's teachings on eschatology to maintain a sound understanding of biblical truths.

In the face of adversity and accusations, Christians must remain steadfast in their faith and convictions. Yielding to pressure to renounce New Testament eschatology would mean compromising on fundamental truths of the Christian faith. Instead, believers should continue to uphold the doctrine of Christ as revealed in the Scriptures, even in the midst of opposition and misunderstanding.

Denying Necessary Inferences of the Second Jewish

Commonwealth Context Distorts Hamartiology

Hamartiology, in simple terms, is the study of sin. It delves into the nature of wrongdoing, exploring questions like why people sin, what constitutes sin, and how it affects individuals and society. Imagine you're diving into a deep pool of understanding, exploring the murky waters of human behavior. Hamartiology shines a light on the darker corners of human nature, helping us comprehend the complexities of sin and its consequences.

Think of it like unraveling a mystery. Hamartiology seeks to uncover the root causes of sin, examining how our thoughts, desires, and actions can lead us astray. It's like peeling back layers of an onion, revealing the hidden motivations behind our behavior.

But hamartiology isn't just about pointing fingers or casting blame. It's about gaining insight and wisdom, understanding the human condition so that we can strive to live better lives. It's like putting together a puzzle, piecing together the fragments of our brokenness to reveal a clearer picture of who we are and how we can grow.

In essence, hamartiology is a journey of self-discovery and reflection, guiding us toward greater understanding and ultimately, redemption. It's an essential aspect of our spiritual growth, helping us navigate the complexities of right and wrong in a world filled with shades of gray. However, in arbitrarily rescending the rules of CENI in respect to the eschatology field of study the real potential for disagreement and discord emerges due to conflicting interpretive approaches and priorities about the importance of Bible prophecy. A lack of consistently applying Necessary Inference (NI) principles can lead to views that sharply deviate from the straightforward claims of Scripture. This creates an environment where merely questioning traditional eschatology feels 'forbidden' and 'sinful' - and confusion enters the picture when the ones accepting Bible prophecy are the 'sinners' and the ones refusing to use the same NI criterion are 'blameless.' Hamartiology is then turned on its proverbial head!

The result is that debates over fulfilled versus future prophecy often generate far more heat than light. Though one side may align with CENI and the explicit timing indicators in the text, majority opinion does not guarantee faithfulness to God's Word. Yet anger and quarrels between believers over disputed interpretive matters can be spiritually unsafe. In this situation, the Bible offers guidance for discerning truth. Just as the Bereans examined the Scriptures daily to see if Paul's teachings aligned with them (Acts 17:11), we must allow God's Word to arbitrate interpretive disputes. While consensus views provide wisdom at times, the Thessalonians are commended not for blindly following majority declarations about end times, but for measuring them against apostolic authority (2 Thess. 2:15).

When it comes to Bible prophecy, we must ensure our conclusions flow from consistent interpretive principles governed by the text itself. Where disagreement exists without animosity, collective truth-seeking in an open yet careful manner is needed. But the Scriptures must judge where faithfulness lies when views fundamentally diverge. Reasoned debate is worthwhile only to the extent it accords with sound handling of God's Word.

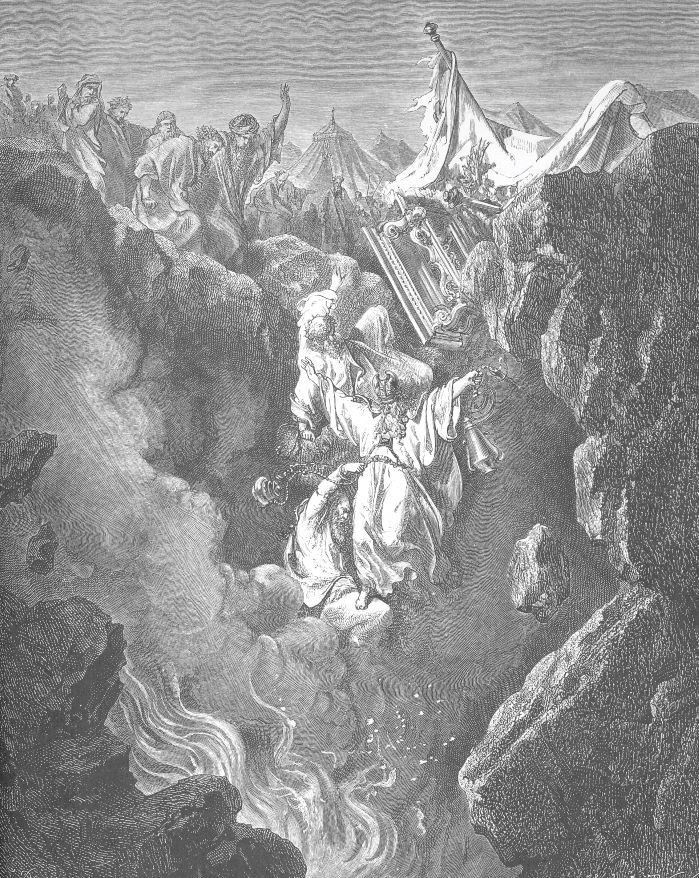

Caption: Korah, Dathan, and Abiram rebelled against Moses' leadership, and as a consequence, the earth consumed them. Similarly, today, there's pressure on Christians to abandon the biblical teachings about the end times from the late Second Temple period. But consider this: Which view truly undermines the authority of Jesus? Is it the belief that he faithfully fulfilled all his promises, or the idea that we're enduring a prolonged "Crisis of Delay and Disappointment" spanning centuries?

Related

Transitioning From a Protestant

Understanding of the Synoptics & John

How the CENI Principle Actually Supports

the Use of Instrumental Music in Worship

Semantic Agreement Between Christians