The Hellenistic Apostasy in Late Second Temple Judæa

and God’s Reaction to “Worldly Wisdom”

by Mark Mountjoy

Scripture text: “And this is the condemnation, that

light is come into the world, and men loved darkness

rather than light, because their deeds were evil”

(John 3:19).

Introductory Remarks

FREQUENTLY, WHEN WE READ PASSAGES from the Bible, we bring assumptions that do not align with the context and history behind them. These assumptions can influence and misshape our interpretation of the events described. To properly understand the meaning behind a passage like Matthew 11:20-24 (specifically verse 25), we must thoroughly comprehend the historical context and any wrongdoing or offenses that may be related.

The scripture text from John 3:19 provides important context -

"And this is the condemnation, that light is come into the world, and men loved darkness rather than light, because their deeds were evil."

Here Jesus explains the reason why men were condemned - not for arbitrary reasons, but because they loved darkness rather than light due to their evil actions. In other words, there were sinful things in their lives that meant more to them than repentance and coming to the light.

Regarding Matthew 11:20-24 and John 3:19 it is important to understand their chronological order. Some interpretations assume that God's rejection is illogical and arbitrary. However, we should ask: Did God predetermine certain Jews to be lost before they were born? Or did the possibility of penalty emerge after Jews strayed from the Law of Moses and adopted the Greek philosophical framework of Epicurus of Samos and other philosophers?

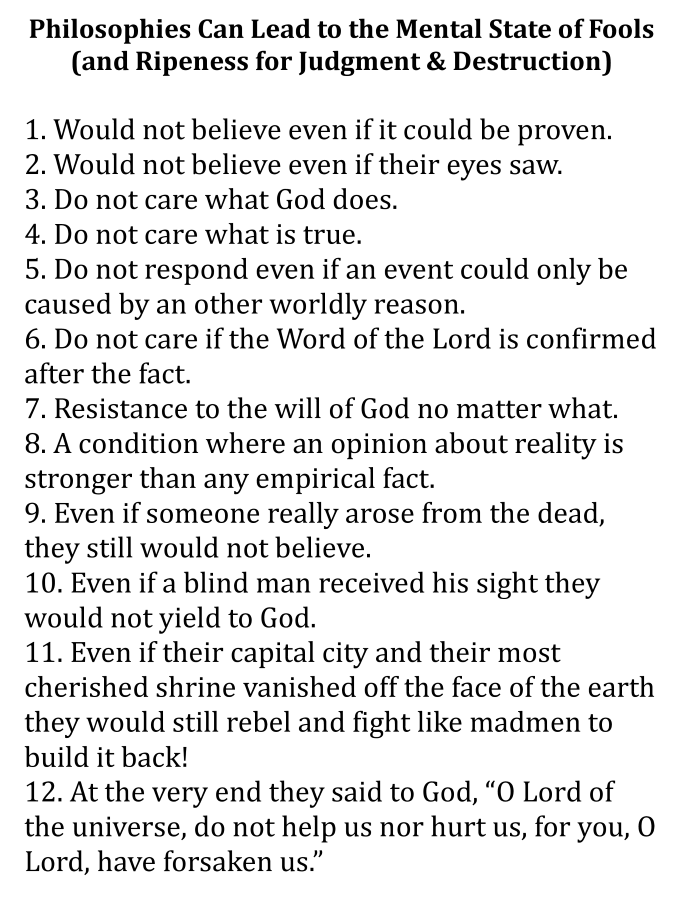

When we realize that the influence of Hellenism, rather than God's eternal decrees, caused the Jewish State to stray from Old Testament beliefs and principles, we understand that this apostasy placed people at a disadvantage and peril, making it difficult to accurately assess Jesus' identity and discern the correctness of His words and actions.

A deviation from their heritage resulted in necessary punishments, as indicated in Deuteronomy 28:15-68 and Acts 3:22-23. However, had they remained faithful to the Law and the Prophets, key beliefs would have given them a foundation for reflecting upon, evaluating, and ultimately accepting Jesus.1 These beliefs include God's ability to intervene in history (Isaiah 19:1 and Daniel 7:13) and perform miracles through His servants (2 Kings 5:1-19), as well as God's personal attention and consistent concern for the world (Psalms 33:13 and Romans 1:18-32).

By reflecting on the abandonment of certain aspects of the Israelite religion, we can understand how God's people got into trouble and why many in the ancient Jewish world were stubbornly resistant to the Gospel. These insights allow us to interpret New Testament passages discussing judgment, culpability, and condemnation differently than we would without this background knowledge.

In first-century Judea, widespread cynicism and even hostility towards Jesus and His miracles was largely due to a worldview that did not accept anything supernatural. For example, unlike many today, at that time many Judeans considered Jesus' many claims, mighty works and miracles not to be good or amazing, but sinister and diabolical (Matt. 12:24 cf. John 8:48; Matt. 27:63). Many rejected their religious heritage affirming events like the flood (2 Peter 3:4) and preferred explanations for Jesus' resurrection involving theft rather than accepting the possibility of a miraculous event (Matthew 28:11-15; Jude 10).2

This dire and sickening un-Israelite way of looking at reality came after the advent of Alexander the Great and his Hellenistic cultural revolution, which brought various philosophical beliefs and conceptual falsehoods against God's revealed will for His covenant people in the Law of Moses. Sadly, these ideas were increasingly embraced by the Jewish masses, including Epicureanism, conceived and spread by Epicurus from Samos. While attractive, it corrupted the Jewish community to such an extent that many refused to believe in angels, spirits, resurrection, miracles, or wonders performed by God (Luke 20:27-38; Acts 23:8), denying fundamental Old Testament assumptions. The Sadducee sect subscribed to borderline atheistic beliefs heavily influenced by Epicurus.

Therefore, it is unsurprising that the cities of Chorazin, Bethsaida, and Capernaum witnessed Jesus' mighty works but doubted them. To understand texts suggesting God predetermined certain individuals' fate regardless of their choices, we must reconsider the historical context. Before concluding these cities were destined to be lost, we must recognize they turned away from God by embracing Epicurus' wicked philosophy, which was not aligned with God's divine truth revealed to their society long ago through Moses and the prophets. This aligns with Jesus's words in John 3:19 - their condemnation was not arbitrary, but because "they loved darkness rather than light" due to their evil deeds and choice to reject God's truth.

Regarding Romans 9:11-24 and its potential interpretation of teaching arbitrary salvation, Romans 11:23-24 provides an important counterbalance. In Romans 11:23-24, Paul states:

"And if they [the people of Israel] do not persist in unbelief, they will be grafted in, for God is able to graft them in again. After all, if you [Gentiles] were cut out of the olive tree that is wild by nature, and contrary to nature were grafted into a cultivated olive tree, how much more readily will these, the natural branches, be grafted into their own olive tree!"

This passage indicates that salvation is not arbitrary, as God is willing to graft the Hebrew people back into the olive tree (representing God's people) if they do not persist in unbelief. This directly contradicts the idea that God predetermined some individuals for salvation and others for condemnation, regardless of their choices.

Paul's metaphor of the olive tree reinforces the principle that those who were once cut off due to unbelief can be grafted back in through faith. The opportunity for salvation remains available to both Jews and Gentiles, contingent on their response to the gospel message.

Therefore, while Romans 9 discusses God's sovereign choice in election, Romans 11:23-24 clarifies that this choice is not arbitrary or unconditional. God's desire is for all people, including the Hebrew nation, to be saved through faith in Christ. Their salvation or condemnation hinges on their persistence in belief or unbelief, not on an arbitrary decree made before their birth.

Endnotes

1 This means that the punishment was a part of a national agreement with God, and had already been predetermined for a certain time period, rather than stretching into eternity.

Additionally, this natural consequence was a result of violating said national agreement, as it had happened to other nations in the past, such as those under King Saul, Jeroboam, and Rehoboam, during the time of divided kingdoms, as well as the Assyrian capture of the Ten Tribes and the Babylonian Captivity of Yehud. It is important to note that the penalty of blindness did not indicate that God had arbitrarily predetermined the fate of any first century Jews, Israelites, Idumeans, Godfearers, or Romans to be cast into the lake of fire, also known as the second death. This can be seen in passages such as 2 Peter 3:8-10 and Jude 23.

2 On the eve of the Destruction of Jerusalem, God performed obvious and blatant signs and miracles that went against all laws of normal nature. For example, a star that looked like a sword appeared above the city, and a comet remained visible throughout all of A.D.63. On the 8th day of Nisan that year, a light shone around the altar in the Second Temple at three o’clock in the morning, and it was as bright as daytime. This lasted for thirty minutes. During that same festival, a heifer being led by the priests to be slaughtered gave birth to a baby lamb in the midst of the Temple. Furthermore, the eastern gate of the Second Temple, which usually required 20 men to open, opened on its own accord. Thirty-seven days later, on the Sunday night of May 8, A.D.63, chariots and troops of soldiers were seen running through the clouds over Judæa and surrounding cities. After that, many heard the voices of a multitude inside the Second Temple saying, “We are leaving this Place.” (Ref. Wars of the Jews 6.5.3.288-300).

Caption: Epicurus of Samos - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia